Do Scramble Crosswalks Really Save Lives?

One of the City of Los Angeles’ ongoing efforts is VisionZero LA, which is an initiative that aims to end traffic-related death by 2035. One of strategies that has been implemented to accomplish this goal is installation of scramble crosswalks around the city.

Typical crosswalks are designed so that vehicles and pedestrians travel together in the same flow of traffic. For instance, when a walk sign is on for pedestrians traveling in North South direction, vehicles are allowed to travel in North South direction as well. At this time, pedestrians and vehicles traveling in East and West directions must wait.

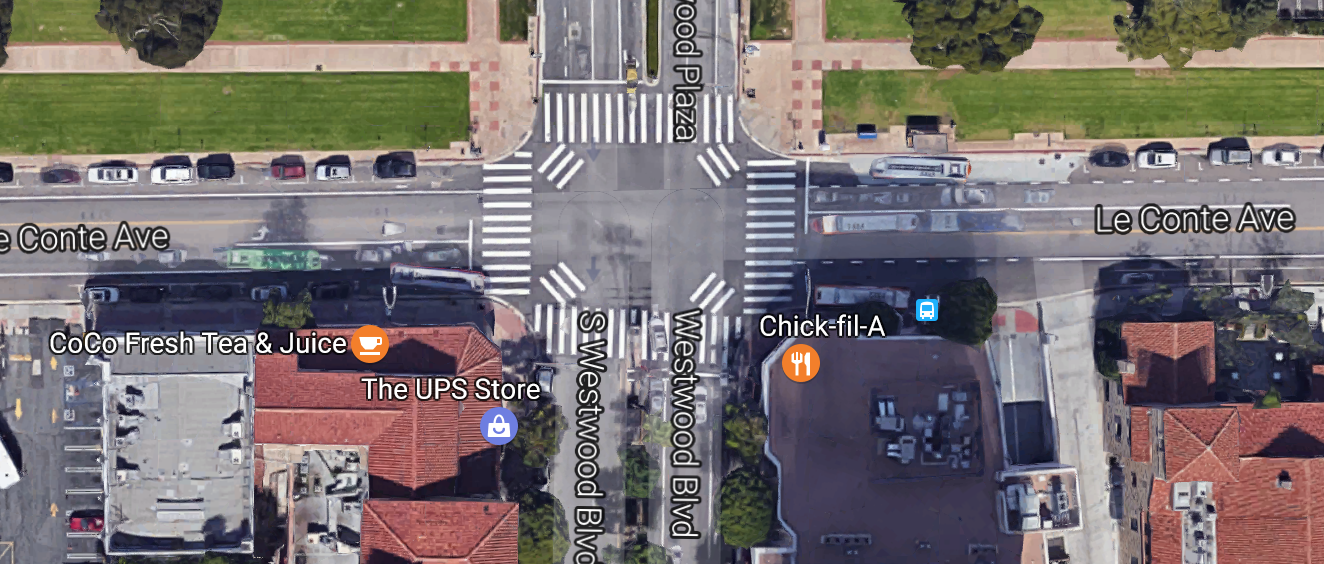

Scramble crosswalks, on the other hand, allow pedestrians to travel in all directions, including diagonally. When pedestrians are crossing, vehicles are not allowed to travel at all. If you are curious about an example, you don’t have to look far. In Westwood there is a scramble crosswalk on the intersection of Westwood Boulevard and Le Conte Avenue.

This may sound like a great idea to ensure the safety of pedestrians. In fact, Los Angeles Magazine published an article titled “L.A.’s New Diagonal Crosswalks Are Literally Saving Lives.”

But are they really?

On one hand, yes. Statistical data shows that installation of scramble crosswalks is actually decreasing the number of traffic related injuries. The prime example is the intersection of Hollywood and Highland. According to VisionZero, the intersection used to have in average 13 crashes per year, but after the installation of the scramble crosswalk in November 2015, there have been zero crashes. This is indeed a significant and promising improvement.

However, one vital piece is missing: accessibility for people with disability. Currently there is no measure in place that requires implementation of accessibility features for scramble crosswalks.

First, scramble crosswalks are challenging for those who are blind and visually impaired. The Guidelines for Accessible Pedestrian Signals published by the National Cooperative Highway Research Program states that scramble crossing “makes it difficult for pedestrians who are blind or visually impaired to recognize the onset of the WALK interval, particularly at locations where right on red is permitted.” This is because in a scramble setting, it is not safe to rely on parallel traffic to determine crossing. Also when there is no vehicle movement, it is hard to determine whether it is safe to cross, because it is difficult to tell where vehicles are. The Guidelines for Accessible Pedestrian Signals recommends that accessible pedestrian Signals (APS) provide more detailed information when the button is pushed. For example, the button could say the following: “Wait to cross Howard at Grand. Wait for red light for all vehicles. Right turn on red permitted.” The installation of APS that provide such detailed information will ensure that blind and visually impaired travelers can cross with greater safety and certainty.

Secondly, safety must be ensured also for those who use mobility aides, such as wheelchairs and crutches. According to this study, pedestrians who travel using a wheelchair have a 36% higher risk of dying from a car-related injury as compared to those not using a wheelchair. Scramble crosswalks should be helpful in addressing this alarming statistic. However, the crosswalks must be made accessible in order for them to be effective. Making crosswalks accessible includes installing appropriate curve ramps and level landing, as well as providing sufficient time for crossing.

So, do scramble crosswalks really save lives?

Yes but not completely. Scramble crosswalks may have been proven to be effective in “saving lives” but the city of Los Angeles must do more so that they become accessible for those with different modes of travel such as white canes, wheelchairs, and crutches.

Miso Kwak is an undergraduate student at UCLA majoring in Psychology with a double minor in Disability Studies and Education Studies. In addition to blogging for the UCLA Healthy Campus Initiative, she plays the flute with the UCLA Woodwind Chamber Ensemble. Outside of school, she works as a mentor for high school students through Accessible Science, a nonprofit organization that facilitates science camp for blind youth.